Learning from the Social Lives of Shoes: A Cultural Approach to Sustainability

The most sustainable shoe is one that never gets thrown away—but what makes people treasure some products while discarding others?

With 22.4 billion pairs of shoes produced annually, the footwear industry faces mounting pressure to become more sustainable. While much attention focuses on materials and manufacturing, understanding how shoes become culturally significant is key to reducing waste and creating more sustainable business models.

In my recently published academic article for the International Journal of Sustainable Fashion and Textiles (May 2025), I revisited my doctoral research with Clarks Originals to explore how a deeper understanding of cultural objects such as iconic shoes can inform sustainability strategies. This industry summary presents the key findings in an accessible format for business practitioners. You can find a button linking to the full article at the bottom of this page.

Culture as the Foundation of Sustainability - a ‘Social Lives’ Approach

Culture is increasingly understood as the foundation upon which all sustainability efforts must be built to succeed. While next-generation materials and manufacturing are well and good, they are pointless if nobody finds the products useful and desirable. In the context of fashion and footwear, a cultural approach to sustainability involves first understanding how products attain cultural value and meaning through their journeys across different contexts and time periods. Then it's about using this information to craft ecologically sustainable products and services that people engage with not because we tell them they should, but because they're relevant to their lives, values, daily rituals, practices and identities.

Footwear presents both the greatest challenge and opportunity for this cultural approach. The industry lags approximately 10 years behind the rest of fashion in addressing ecological impacts, constrained by complex materials, manufacturing processes, and durability requirements. Yet this complexity makes footwear the ideal testing ground—if we can crack the sustainability code for shoes, we can unlock solutions applicable across other product categories.

The key lies not in technical fixes alone, but in understanding how certain shoes move beyond their basic function to become meaningful cultural symbols that people treasure. Shoes, like people, have 'social lives' and 'biographies'. Inspired by the anthropological studies of Arjun Appadurai and Igor Kopytoff, my research demonstrates that by tracing these lives, we can learn valuable lessons that enable the creation of products and brands that endure both emotionally and physically.

Through my study of the social lives of the Clarks Originals styles (the Desert Boot, Desert Trek, and Wallabee), I discovered that they have become what Professor Sophie Woodward has termed 'accidentally sustainable'— they have transcended their status as mere commodities to become cultural objects with profound meaning for their wearers. When products achieve this level of significance, people are motivated to keep them longer, care for them better, and take the time to dispose of them respectfully. This opens doors to alternative business models and a service-based economy that ensures sustainable innovation works with and contributes to culture.

The Desert Boot's Cultural Journey: A 75-Year Case Study

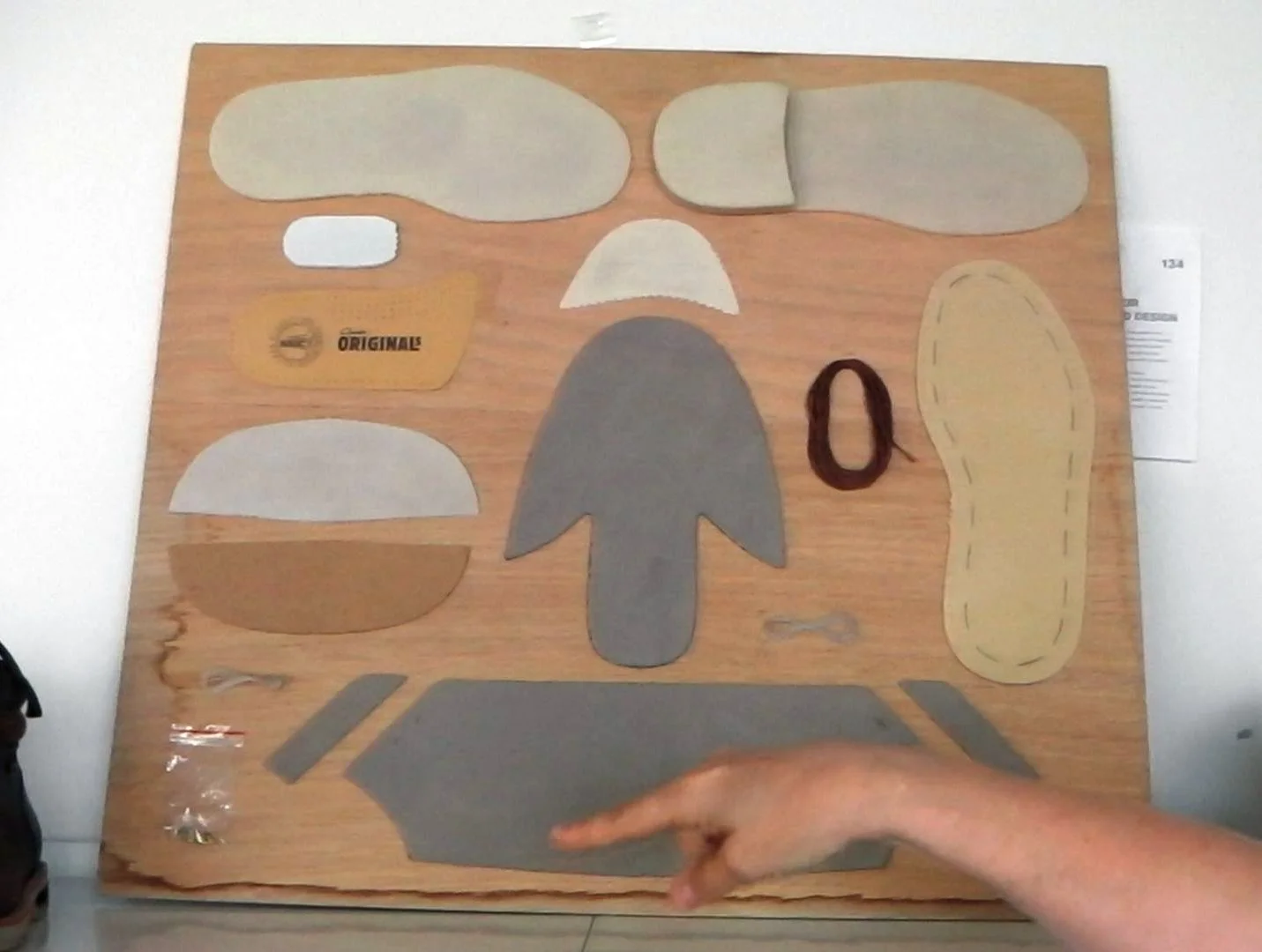

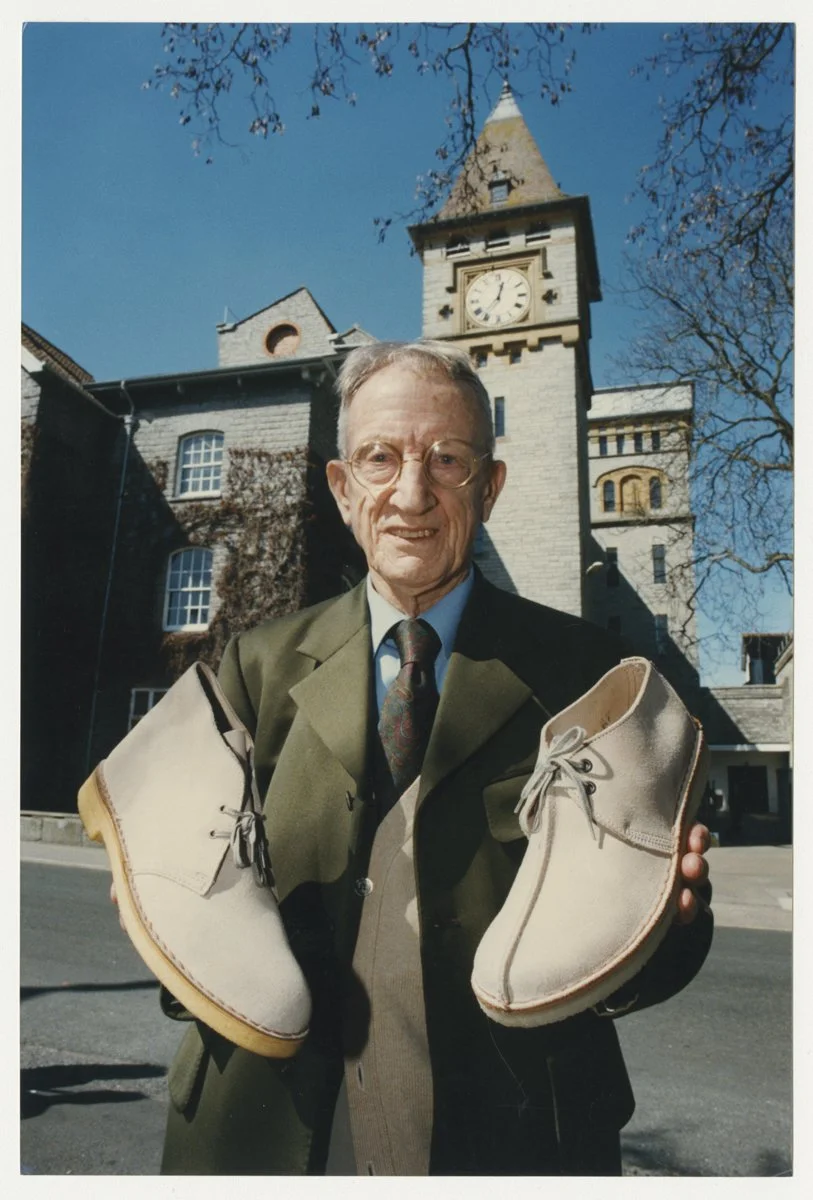

The Desert Boot's 75-year journey illustrates these principles in action. First introduced in 1950 by fourth-generation Clarks family member Nathan Clark, after spotting them on the feet of officers during military service in Burma in 1941, the Desert Boot—the original Clarks Originals—has remained relevant across generations and cultures, with the Desert Trek and Wallabee following similar trajectories.

The success of the Clarks Originals styles isn't just about design - it's about how different groups have made them their own and the stories that emerge through these adoptions. From Jamaican rude boys in the 1960s, to British Mods, American hip-hop artists and the UK Indie music scene, each group has given the Clarks Originals styles new meaning. These stories contribute to cultural vitality - the ongoing process of creating and sharing meaning that keeps culture alive and evolving.

The shoes' material properties play a crucial role in these stories. Of particular note is their distinctive crepe rubber soles which enable different cultural practices, values and rituals that are situated in particular places and times - from the "stealth" valued in post-independence Jamaica and discussed in Al 'Fingers' Newman's 2012 book 'Clarks in Jamaica', to the characteristic "shuffle" associated with the Northern UK indie music scene. Even perceived flaws (like being slippery in the rain) have become part of their character, with material qualities contributing to both practical and symbolic value. As many will have experienced first-hand, it isn't until a brand makes a material or structural adjustment to a popular shoe that we realise the value of such nuances.

Implementation Framework: Building Cultural Capital

My research with Clarks revealed how the ability to sustain the cultural significance of one's products requires building cultural capital through three key types of knowledge:

Material Knowledge: Understanding how physical properties like materials, construction, and design affect use and meaning

Cultural Knowledge: Recognising how products acquire meaning in different places and contexts, and how to engage respectfully with diverse cultural perspectives

Social Knowledge: Building and nurturing genuine connections with users and cultural intermediaries, while gaining insight into their worlds through ongoing engagement

Designers, range managers, and marketing executives who work in step with one another, and with cultural custodians, like archivists and historians, or intermediaries, can embody and incorporate this kind of knowledge – known as cultural or social capital. This helps them create more authentic products and campaigns that resonate deeply with consumers.

Clarks Originals continue to demonstrate this today, but the example I use in the paper is the 2012 'Originals Remixed' campaign – which commemorated the Desert Trek's 40th anniversary and the 50th anniversary of Jamaican independence through a partnership with reggae music label Trojan Records and four contemporary DJs from their key markets in the United Kingdom, America, Italy, and Japan to remix the iconic reggae track 'Let Your Yeah Be Yeah' by the Pioneers. Through a careful process of listening, observing and validating, the team demonstrated how collaboration can enable meaningful cultural exchange rather than appropriation, creating new stories while honouring existing ones.

Practical Strategies for Brands

Several key insights emerged from my research that brands can apply immediately:

Embrace Creative Exchange: Sustainability challenges require creative responses. Through storytelling and collaboration, brands can create meaningful dialogue between different cultural perspectives, leading to innovative solutions that respect both cultural and environmental resources.

Listen More Than You Speak: The most successful initiatives come from deep listening and observation. Develop and protect processes that enable the validation of ideas across different markets and cultural contexts before launching initiatives.

Encourage Organic Growth: While brands must protect their intellectual property, overly controlling how people use and interpret products can hinder cultural vitality. Shoes frequently find themselves on the most unlikely feet and in unexpected places—these are natural aspects of their social lives that enhance their cultural significance. Success often arises from acknowledging rather than controlling how products exist in the world.

Invest in Cultural Knowledge: Allocate time for employees to develop a deep understanding of cultural values and practices. This might involve visiting archives, spending time in stores, talking to customers, or engaging with the communities within which one's products have become entangled. Better still, ensure relevant cultures and identities are represented in your workforce.

Balance Heritage and Innovation: Utilise archives and heritage as resources for creative inspiration while allowing products to evolve alongside contemporary culture. The Alfred Gillett Trust (also known as the Clarks archive) provides an essential resource for the creative teams at Clarks, while continuing to remind them of the brand's legacy, values, and DNA. Recent collaborations demonstrate how understanding cultural history and brand heritage can inform authentic innovation.

The Business Impact: When Culture Drives Sustainability

Another finding from the research is that cultural capital is just as important for a brand's corporate culture as it is for maintaining the value of its products for consumers. Within Clarks, iconic styles had become symbols of brand identity and corporate values. Employees who developed deep cultural and material knowledge of their shoes gained a sense of purpose that went beyond merely responding to spreadsheets and sales targets.

By listening to customers' stories, exploring archives, and understanding the cultural significance of their products, employees became more invested in their work. This fostered ongoing learning, connection with others, and a sense of belonging. Storytelling (internally and externally) cultivates a healthier corporate culture that sustains meaning for both producers and consumers.

The success of iconic products like the Desert Boot, Desert Trek and Wallabee suggests an alternative to the constant churn of new styles. When products become culturally significant, they transcend being mere commodities to become part of how people express identity and achieve a sense of belonging. This cultural value translates into both commercial success and reduced environmental impact through:

Longer product lifecycles

Opportunities for repair, restoration and resale services

Stronger emotional connections with products

More conscious consumption and disposal patterns

Most importantly, the research suggests that sustainability isn't just about materials and manufacturing—it's about creating products that matter to people. When people care about products, they tend to keep them longer, repair them when they break, and think more carefully about disposal and the afterlives of products.

Avoiding 'Culture Washing': The Risks of Getting It Wrong

Just as brands can fall into the trap of 'greenwashing' with superficial environmental claims, there's a growing risk of what we might call 'culture washing' - where cultural storytelling becomes merely a trend or marketing tool rather than genuine engagement with cultural meaning and exchange. This happens when brands:

Treat culture simply as a trend to capitalise on

Lose touch with how their products are actually being used and interpreted in the world

Fail to maintain authentic connections with communities and cultural intermediaries

Over-commercialise cultural significance

Become disconnected from their heritage and values

Try to control rather than participate in their products' social lives

When brand and consumer values become misaligned or when companies lose touch with the evolving cultural significance of their products, it can lead to damaged relationships, lost authenticity, and, ultimately, reduced relevance and dead stock. The key is to maintain genuine engagement with the social lives and emerging biographies of products through sustained investment in cultural knowledge and understanding.

Next Steps: Key Questions for Implementation

For brands looking to enhance their cultural understanding as a way to develop sustainability strategies, start by asking:

How do your products acquire meaning for different groups? If you don’t know, how might you find out?

Which of your products have diverted from their intended paths, or confounded market and trend data and predictions?

Are you giving your team time and resources to develop a deep understanding of the cultural value of your products and brand?

What opportunities exist to tell meaningful stories about manufacture, use, repair, reuse, and recycling?

How might greater transparency of product social lives enhance corporate culture and a sense of purpose and belonging for teams?

How might qualitative insights into product use and disposal inform sustainable innovation and alternative business models?

The Path Forward

The path forward is clear: brands that invest in understanding and nurturing their products' social lives will build stronger, more sustainable businesses. In today's market, authenticity isn't just about heritage - it's about creating meaningful connections between products, people, culture and the environment across the full value chain. By understanding how products become culturally valuable and working with rather than against their social lives, brands can create more sustainable futures while contributing to cultural vitality through creative exchange and storytelling.

This cultural approach to sustainability is not a quick fix—it's a fundamental shift in how we understand and create value. The investment pays dividends not in immediate sales spikes, but in the kind of brand equity and customer loyalty that sustains businesses for generations.

If you've enjoyed this summary, please access the full version using the link below this article. GBP 29.95 or free via institutional subscription.

This summary has been revised for clarity and accessibility from the original article published in May 2025. I acknowledge the use of Claude Ai for assistance in summarising key points and translating for a non-academic audience.

Hear Alex discussing the research in an interview with Michael Ratcliffe for Seamless by PI TV