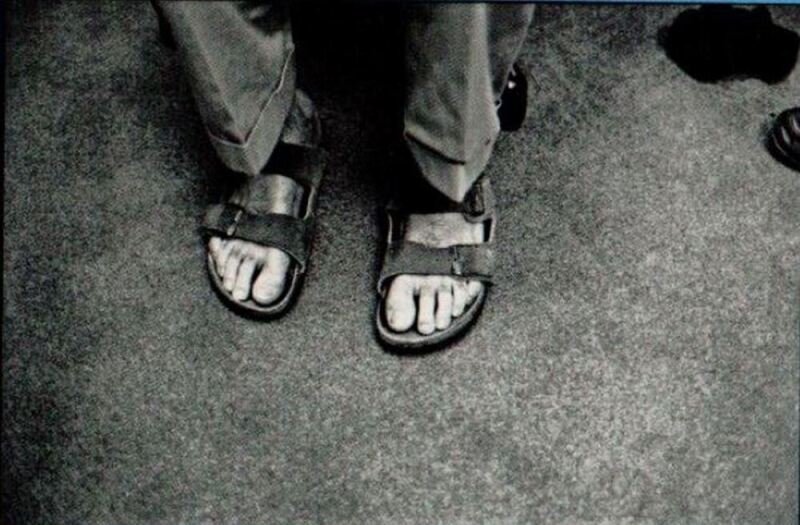

Steve Jobs’ $220,000 Birkenstocks

Earlier this month Steve Jobs’ iconic Birkenstock sandals were sold at auction for an incredible $218,750. Reportedly worn in the seventies and eighties during many pivotal moments in Apple’s history the sandals were well-used, the cork and jute footbed bearing the indelible imprints of his feet.

The relationship between Jobs and his Birkenstocks is well documented and bears a resemblance to relationships between other popular media personalities and their footwear (think Kurt Cobain and the Converse Chuck Taylor, Liam Gallagher and the Clarks Desert Boot, Michael Jordan and the Nike Air Jordan…). According to the auction website, in an interview with Vogue titled Apple Meets Birkenstock, Jobs’ ex-partner, Chrisann Brennan explained “the sandals were part of his simple side […] he was convinced of the intelligence and practicality of the design […] And in Birkenstocks, he didn’t feel like a businessman, so he had the freedom to think creatively.”

Jobs’ relationship with his sandals demonstrates what anthropologists might describe as their ‘inalienability’ (Weiner, 1992): how objects and their users ‘make’ one another and therefore become inseparable. Rather than being something we wear to communicate a pre-formed identity, objects like shoes are understood to be the very medium through which we can make and know ourselves – something Ellen Sampson also writes about in her book Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear. In this sense, objects can become symbolically attached to their owners and that attachment persists even when they become separated.

In capitalist consumer cultures, it is often the case that iconic shoes develop an inalienable connection with a media personality, a process that happens through practices of endorsement. Through wear and social interaction in publicly visible contexts the identities of the wearer, material shoe and brand transfer to one another. This transference is more authentic and successful when unsolicited by the brand, for example when the wearer chooses to wear the shoes rather than when they are paid to do so. In what might be described as a reciprocal exchange, both the wearer and the brand gain value and meaning from an association that materialises through the wearing of the shoes.

The close relationship between Jobs and his Birkenstocks, therefore, has commercial value; through buying and wearing we can literally ‘walk a mile’ in his shoes, enabling a process of identification with him and the values he represents. But while Jobs’ endorsement of Birkenstocks may have increased their share value, the value of his actual pair of shoes is more complicated and speaks to something more sacred, even religious.

The inalienability of shoes and their wearers is something many are faced with when a loved one dies and is the reason we may find it difficult to dispose of their shoes – particularly when that person was known to wear one particular pair or style of shoe, as was the case with Steve Jobs. Anthropologist Alfred Gell coined the term ‘distributed personhood’ to describe the way we are dispersed beyond our body boundaries amongst material objects, tracings and leavings which go on to testify to our existence (Gell, 1998). Shoes are particularly powerful in this respect because they take the shape and absorb the traces of the wearer’s foot – as synecdoche, they are a part of the wearer that comes to represent their whole. In life, but particularly in death the ability of particular shoes to stand in for the wearer ensures their sacredness; destroying them is often unthinkable and may even feel like a second death.

In death, we may think of these objects, then, as relics in a more religious sense and the frequent auction of deceased celebrities’ belongings points to connections that can be drawn between consumer culture and religious belief more broadly. It is widely held that the scientific and rational thought brought about in Western societies during the Enlightenment period resulted in increasing secularism. Despite this, often the most atheist amongst us still require a religious valorisation of the world, a reason for our existence, a purpose or fate, and a sense that there is a plan. In his book Illusions of Immortality: A psychology of Fame and Celebrity, Giles goes so far as to claim that celebrity culture is a kind of replacement for organised religion (2000): where previously saints and deities may have been a focus for worship, today it is often media personalities and cultural icons.

As explained elsewhere, one tangible aspect that both religion and celebrity culture hold in common is the ‘hierophany’, a term coined by philosopher Mircea Eliade to describe the sacred in physical form (1957). In both a secular and religious sense a hierophany might be a place of pilgrimage or an object that has been touched by or is part of the deceased (e.g. hair, bone or even shoes). These objects are valuable because they are considered contagious, the person’s qualities or essence are understood to have transferred to the object through touch and in death that can be perceived as a conduit or way to connect with the divine (Newman et al. 2011).

In life, many certainly worshipped Steve Jobs and in death, the few belongings he owned have become part of a closed set: rare, irreplaceable and sacred. In a religious sense, it is difficult to deny the visual similarities between Jobs’ sandals and those we might imagine Christian prophets to have worn–the traces of the feet perhaps comparable to those left on the Turin Shroud. One might even go as far as to claim Jobs’ identity as Prophet for the Apple brand – itself a kind of secular religion through which a sense of community, moral philosophy, beliefs and practices are shared (are you Apple or Microsoft?). Whatever one’s interpretation, the sale of Jobs’ sandals evidences the inextricable relationship wearers have with their shoes, one that in certain circumstances can become immensely valuable, powerful and even sacred.

References

Eliade, M. (1957). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, New York, Harcourt.

Gell, A. (1998). Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Giles, D. (2000). Illusions of Immortality: A Psychology of Fame and Celebrity, Basingstoke, MacMillan Press Ltd.

Newman, G. E., G. Diesendruck, and P. Bloom. 2011. Celebrity Contagion and the value of objects. J. Consumer Res. 38(2): 215–228.

Sampson, E. (2020). Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear, London, Bloomsbury.

Sherlock, A. (2013). Larger Than Life: Digital Resurrection and the Re-Enchantment of Society. The Information Society, 29, 164-176.

Weiner, A. B. (1992). Inalienable Possessions: the paradox of keeping-while-giving, Oxford, University of California Press.