Footwear in former colonies: new steps for researching shoes, their meanings and uses in 19th-century Americas (1780-1920)

The ability to reflect on everyday life during colonialism is essential to understand its impacts and legacies today. The 19th century in the Americas is an ideal period and place to explore the conflicts between the Ancien Régime, the (controversial) adoption of modern values (including civil rights, individuality, and leisure), and the transformation of production.[1] The study of shoes provides a wonderful opportunity to gain insights into the social and cultural impacts of colonisation and industrialisation during this time.

My research started with a few questions about the role of shoes in Rio de Janeiro. At the time, Rio was an important city with a very unequal, slavery-based colonial society. I asked myself: “what kind of pairs were available in the city? How were they made, and by whom? Who bought them, and how?”.

The results were published in my first book, Barões de Tamancos: uma história social dos sapatos no Rio de Janeiro (1808-1914), (translated as Barons Wearing Clogs: A Social History of Shoes in Rio de Janeiro), and the answers to these questions do not come in a linear way. Instead, each chapter explores the connection between shoes and different aspects of social life, which were under stark transformation, such as the idea of freedom, the work associations and their connection to paid work, leisure, independence, and the local perception of opulence, among others.

The discussion goes beyond the city of Rio, eventually connecting different spots in Brazil and elsewhere. To do so, the book contains more than 200 images, from pictures of different pairs to newspaper ads and artwork from different countries, including (but not limited to) Brazil, Chile, France, and Mexico.

At first sight, shoes appear largely absent from historical sources concerning the Americas, yet on closer inspection, their significance shines through. Many authors insist that, in different locations, being barefoot was the symbol of a lack of liberty for the colonised.[2] The appearance of shoes in various contexts suggests there are many stories left to explore that add complexity and nuance to this narrative.

The shoe production scenario at the time was quite intense. At the beginning of the century, shoemaking was mostly a workshop-based artisanal practice that demanded a wide set of skills, with one person (most likely) making the entire shoe. Its presence in the colonies is often contradictory; while it highlights the remarkable economic and social potential of various locations, local production also faced threats from imported metropolitan finished goods.[3]

The expectation of enslaved people to walk barefoot seems to be a reality in different places, including Brazil and the Caribbean, so, at first, we might assume that the different colonies would have a low demand for shoes since a large part of the population (sometimes over 50% of a town or city) would not use them. [4] However, the opposite was true, with a strong demand alongside a significant presence of shoemakers and shoe workshops/stores. By 1875, Britain produced 5.5 million pairs of shoes per year, and it was expected that the British colonies would absorb 90% of this production.[5]

In Cuba, by 1850, the shoe industry had 4000 employees, of which 15% were enslaved people.[6] By 1862, there were 796 shoe stores in the entire island. Several shoe professionals who worked in the Americas were immigrants, from countries such as Spain, Italy and France,[7] but locals (free and enslaved people) were also part of this industry.

The influence of globalised fashion is also undeniable. European fashion, especially from Paris, developed a consolidated position as the central aesthetic reference, with pairs that were either imported or copied by local stores.[8] As soon as 1822, an ad from the newspaper Diário do Rio de Janeiro announced that a city shop called the French Warehouse (“Armazém Francês”) “[...] received a beautiful collection of [imported] shoes for ladies [and] silk stockings”.[9] In the USA, until the 1850s, French references were valued to the point that a Broadway shoemaker decided to describe his own creations as imported from France instead of locally made.[10] In her book Viaje a La Habana (A trip to Havana), from 1844, the countess of Merlín states that “[...] one habanera [girl from La Habana] never uses twice her ball outfits, even if they are very luxurious, and coming from an expensive shipping from Paris; however, a young lady would rather not attend the ball than present herself a second time with the same attire”.[11] By the early 20th century, the British company C&J Clark Ltd. would start selling its shoes in Jamaica, creating a particular tie between the brand and the country.[12]

The artisanal warehouses were progressively replaced by industrial structures with heavy machinery, thus impacting the shoemakers’ traditions and perspectives and creating new organisational possibilities. Yet shoemakers were far from passive victims of industrialisation, often seen by newspapers and other publications as an organised category, able to manage strikes and negotiations. The presence of anarchists in the shoe industries in the beginning of the 20th century[13] marks the legacy of a long history of political positioning noted since the 18th century.[14]

Historic shoe research is as challenging as it is interesting. Existing studies often pick a starting point to “create an aesthetic timeline of shoes”,[15] yet there are fewer organised archives about shoes than we might expect. The shoes themselves are possibly the easiest element that one can find. In this sense, museums are incredible allies: different institutions offer a good sample of pairs. Often missing from these collections, however, are the wider stories they represent – the context during which they were bought, the buyer’s intentions, the shop’s dynamics, and so on.

To account for this gap, other materials can be very helpful: shop invoices, newspaper ads, magazines, pictures, correspondence, etc. One piece of evidence that I’m particularly fond of are paper etiquettes (labels) on the inside of early 19th-century shoes. They indicated the shoemaker/store where the shoe came from and were heavily stylised. In Figure 1, we have a shoe from Melnotte[16], commonly called ballerine. It was a usual model of the time (reminiscent of contemporary ballet pointes).

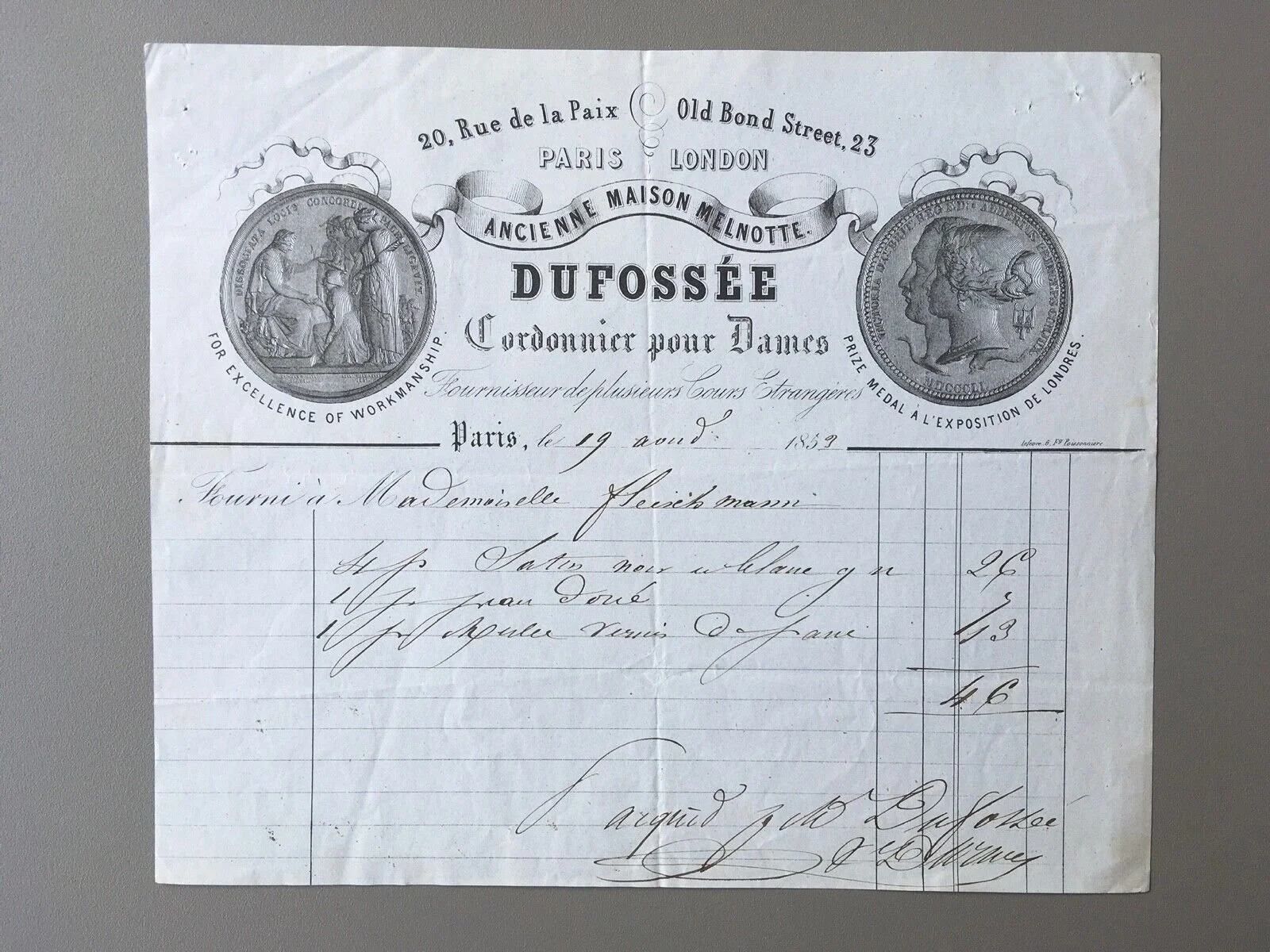

In Figure 2, we can see an invoice by Dufossée, Melnotte’s successor in the 1850s.[17] Invoices are central research sources since they provide evidence of a concrete transaction. Through them, it is possible to track entire families and their consumption habits, check which kind of goods were sold in the stores and how people paid for them, and confirm a store’s address, among other topics. In this case, Mademoiselle Fleischmann bought four pairs of satin shoes (black and white) and other items. The paper features of the invoice also matter – it was printed but filled by hand. This suggests that the store is important enough to expect a large volume of sales, but there is no selling automation yet. Part of the printed space is filled with mentions of international prizes in Universal Exhibitions and Dufossée’s connections to royal courts, thus enhancing the importance and legitimacy of the shoemaker as a distinguished professional (who may charge accordingly). Although these are objects from France, due to the striking impact of Parisian references in the elite taste, both the shoe and the invoice can be seen as ideal examples that would be either imported by the colonies or used as an inspiration for local production.

If silk was the primary material used in the early 19th century, the Belle Époque witnessed the quick adoption of resistant leather, which became easier to work with due to the development of machinery and chemical solutions. Elastic, rubber and other synthetic materials became widespread, and a pair of boots from Rio contains these three elements in a common combination of the early 20th century (Figure 3). This is a good example of a mix of urban elegance and standardisation in high-volume production since the boots are probably ready-to-wear. Tailored demands, mandatory in the first decades of the century, would become a luxury for most customers. The stores also drift apart from the shoemakers and increasingly become a point of sale for different producers.

Figure 1 - Shoe. Paper label on insole: “M No 19 Rue de la Paix, près le Boulevard des Capucines, MELNOTTE, Mḍ Cordonnier pour les Dames, à Paris”. Circa 1830. Victoria and Albert museum, London, inventory number T.23-1937.

Available at: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O356532/shoe/. Last seen April 5, 2024.

Figure 2 - Invoice by Dufossée, August 15, 1853. Property of the author.

Figure 3 – Leather boots with side elastics and textile label, from the early 20th century. Label says: “J. T. Machado & Cia., Rua do Hospício, 28B”, an address in downtown Rio. Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, inventory number 18620-21. Picture by the author.

The reconstitution of shoe stores, their clientele and their taste, the adoption of different industrial processes and their economic challenges is a complex puzzle. Its solution involves dealing with different sources, from shoemakers’ union documents to portraits or works of art that might bring a fascinating depiction of fashion trends.[18] Illustrators held an important role in this day-by-day register.

In Figure 4, we can see Jean-Baptiste Debret’s interpretation of free black women in Rio during the 1830s [19]; this depiction suggests the role of shoes as an indicator of freedom. At the same time, the ballerines highlight the fast circulation of fashion references and the presence of Parisian taste. The woman wearing a grey skirt with a chevron decoration is wearing ballerines similar to Melnotte’s pair from Figure 1. Moreover, the facade of the building indicates “French fashion” (“Modas Francês”); that is, she is at the entrance of a store that probably sells items either imported from France or following French fashion.

Isaac Mendes Belisario included the drawing of a Milkwoman (figure 5) in his Sketches of Character from Victorian Jamaica. This working woman is seen barefoot in a tropical landscape. Artists like Debret and Belisario were interested in depicting typical scenes to describe, according to their perspective, the local day-by-day and its common compositions. While we don’t know if the Milkwoman is a free person or not, Belisario’s work intends to stress that, at the time, spotting a barefoot black woman in rural Jamaica would be something plausible.

Finally, in the painting by Paul Harro-Harring (Figure 6), two sailors are negotiating with three sellers, but the sitting woman stands out. She is wearing shoes with buckles, often even more expensive than the actual shoes due to the amount of metal or stones. This reinforces the message of a free woman—independent yet subtle enough not to confront other social norms of the time, such as female modesty and dignity, as she reveals just enough of the shoe for us to notice her covered foot and the buckle. Indeed, in different colonial scenarios, long skirts were the norm and female legs were not expected to be shown.[20]

Figure 4 – “Free black women who live from their work”. Source: Debret, 1834-1839, vol.02, planche 52.

Figure 5 – Milkwoman. Source: Belisario, 1837-1838, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, folio A 2011 24.

Figure 6 – Scene in a selling spot: sailors negotiate with black women. Paulo Harro-Harring, oil on canvas, 1843, 31 x 39 cm, collection Paulo Harro-Harring/Acervo Instituto Moreira Salles. Code 003HH01564.

These are only a few samples of different works with strong research potential. So far, it is striking how different places, with their own colonial experience, can be brought together by the strength of fashion tendencies and structural processes. Just as shoes were central in different places to mediate freedom and slavery, tastes were heavily imported, and the shoes were quite similar, with local twists. The importance of decorative buckles could be seen in Peru[21] and Brazil. Strikes mattered, as seen in the episodes of Lynn, Massachusetts, or Rio de Janeiro. There is still a lot to find out about the clients and the development of a “brand grammar” – during relevant situations, such as weddings, ladies from Chile seem to have relied upon foreign references to build their “bridal look”[22] and travels to major fashion centres were seen as an opportunity to curate a wardrobe.[23] Shoes were then an excellent example of how global processes influenced local practices and tastes; different references were, at the same time, local and global, distant and close.

There are still many pieces of this puzzle to join – be it to better understand importation strategies, the migration of shoemakers themselves, the political impact of new production flows, or even the perspectives of caring customers who didn’t have the heart to throw their pairs away.[24] Thanks to them, we can start rebuilding these scenarios, sometimes 200 years after they happened.

Notes:

[1] SOARES, C. E. B. (2023) Barões de Tamancos: uma história social dos sapatos no Rio de Janeiro (1808-1914). Rio de Janeiro: Author’s edition.

[2] ALENCASTRO, L. F. (2019). História da vida privada no Brasil. Império, a corte e a modernidade nacional. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

[3] SOUGY, N. (2012) Le négoce transatlantique des produits de luxe (XVIII-XIXe siècles). Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques, 133-36, pp.27-38. Available at: https://www.persee.fr/doc/acths_1764-7355_2012_act_133_6_10407. Last seen November 23, 2024.

[4] BERGAD, L. W. (2007) The comparative histories of slavery in Brazil, Cuba and the United States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[5] MIRANDA, J. A. (2004). American Machinery and European Footwear: Technology Transfer and International Trade, 1860–1939. Business History, 46(2), 195–218. doi:10.1080/0007679042000215106.

[6] SARMIENTO RAMÍREZ, I. (2000) Vestido y calzado de la población cubana en el sigo XIX. Anales del Museo de América, no. 08, pp.161-199. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=1455993. Last seen November 23, 2024.

[7] The Brazilian National Archives hold several lists of immigrant shoemakers, which were registered by the Court Police when their ship reached the country. See Arquivo Nacional, BR RJANRIO 0E.COD.0.381, v.7/f.030v – item; BR RJANRIO 4J.COD.0.773, v.01 – Dossiê.

[8] REXFORD, N.E. (2000). Women’s shoes in America, 1795-1930. Kent, The Kent State University Press. One example of non-French reference is the Czech brand Bat’a, which had a striking presence in the Caribbean. See PERUTKA, L., BALABAN, M., HERMAN, J. The Presence of the Baťa Shoe Company in Central America and the Caribbean in the Interwar Period (1920-1930). (may,-aug, 2018) Am. Lat. Hist. Econ, 25 (2), pp.42-76, https://doi.org/10.18232/alhe.v25i1.897.

[9] In 1822 the French Warehouse was located in downtown Rio de Janeiro, at rua do Ouvidor, 47. Diário do Rio de Janeiro, November 9, 1822, p.04-05. Available at: https://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=094170_01&pesq=sapato&pasta=ano%20182&hf=memoria.bn.br&pagfis=2418. Last seen November 23, 2024.

[10] REXFORD, Women’s shoes in America, 1795-1930, p.38.

[11] SANTA CRUZ Y MONTALVO, M. (1981) Viaje a La Habana. Madrid: Amalía E. Bacardi, p.233-234. Translated by the author. Original quotation: “[...] una habanera no usa nunca dos veces sus trajes de baile, aunque son de gran lujo, enviados a gran coste desde París; pero una joven preferiría no ir al baile si tiene que presentarse por segunda vez com el mismo traje”.

[12] FINGERS, A. (2012) Clarks in Jamaica. London: One Love Books.

[13] HELMS, R. P. (2006). George Brown, the cobbler anarchist of Philadelphia. London: Kate Sharpey Library; NEVES, M.C. (apr.-jun. 1973). Greve dos sapateiros em 1906 no Rio de Janeiro: notas de pesquisa. R. Adm. Emp, 13 (02), pp.49-66. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rae/v13n2/v13n2a04.pdf. Last seen November 16, 2024.

[14] HOBSBAWM, E. J., & SCOTT, J. W. (Nov 1980). Political shoemakers. Past & Present, 89 (1), pp. 86-114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/past/89.1.86.

[15] BOSSAN, M.-J. (2004). L’art de la chaussure. New York: Parkstone.

[16] An important shoemaker from Paris during the first decades of the 19th century, which had a pioneer take on international expansion and opened a new store in London as soon as 1828.

[17] The idea of succession was quite present during the 19th century. By presenting themselves as “sucessors” of a well-known shoemaker, new professionals could legitimate themselves and even buy their master’s infrastructure (the workshop’s tools, etc) while (hopefully) inheriting their clientele. Dufossée did work with Melnotte and another associate, Müller, from who we know little of. After Melnotte’s death in 1851, Dufossée seems to have worked on his own.

[18] RIBEIRO, A. Fashion and Fiction. Dress in Art and Literature in Stuart England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

[19] The Brazilian case is peculiar in American colonial history, because, contrary to other colonies, the Portuguese Royal Family actually moved to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 and intended to reorganise its empire in this new capital. Although this project never reached its purpose, and the Royal Family went back to Portugal in 1821-22, it had strong impacts since several political and economic decisions intended to bring more focus to local development. See SCHWARCZ, L. (1999). As Barbas do Imperador: dom Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

[20] SOARES, Barões de Tamancos.

[21] MIDDLETON, J. (2018). Their Dress is Very Different: The Development of the Peruvian Pollera and the Genesis of the Andean Chola. The Journal of Dress History, 02 (01), 87-105. Available at: https://dresshistorians.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-Journal-of-Dress-History-Volume-2-Issue-1-Spring-2018.pdf. Last seen November 16, 2024.

[22] ESPINOZA, F. (2013). Zapatos femeninos. Seducción paso a paso. Santiago do Chile: Museo Historico Nacional. Available at: https://www.mhn.gob.cl/618/articles-37579_archivo_01.pdf. Last seen November 16, 2024.

[23] BLOCK, E. L. (2021) Dressing up: the women who influenced French fashion. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

[24] It is important to note that shoe scarcity is a general museum phenomenon. Usually, simpler shoes are just thrown away because they were too worn off to keep on being used. This creates a considerable bias because general shoe collections will tend to keep pairs developed for the elite, usually in noble materials and with little use. People also tend to keep pairs that were emotionally important to them – hence the relevance of wedding or christening attires, with the exception of military boots, which are often kept as a symbol of conquest and power. See MCCORMACK, M. (2024). Embodying the history of shoes: footwear and gender in Britain, 1700–1850. In E. Craig-Atkins, & K. Harvey, The Material Body. Embodiment, History and Archaeology in Industrialising England, 1700-1850 (pp. 81-99). Manchester, Manchester University Press.